Storytelling with sari‘s volcanic creator is Bengali-American artist, environmental activist and lawyer Monica Jahan Bose. In 2013, she embarked on the project in collaboration with the women of her ancestral maternal village Katakhali, on the island of Barobaishdia, in Bangladesh, to document the struggles and accomplishments of a small remote community at the forefront of the fight against the consequences of climate change.

Faced with seemingly insurmountable difficulties, the resilience of the women of Katakhali is an example of the fundamental role of women in fighting the changes taking place.

In many developing countries, despite a minimal contribution to global warming, women suffer disproportionately from its impact, because of the unequal distribution of resources. It is now universally recognized that their leadership will be essential in addressing the climate emergency.

Since its creation, Storytelling with saris has traveled extensively, bringing the stories of Kathakali women to the United States, Bangladesh and Europe. Participants involved in collaborations through workshops, are invited to write thoughts and promises about the saris. Women in Bangladesh will then wear these ‘climatic promise’ Saris.

Art actions with woodblock prints, writing, oral history, performance and film, exhibitions and workshops took place in Hawaii, Iowa, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington, D.C., California and Wisconsin in the United States; Dhaka and Katakhali in Bangladesh; in Paris, France, in Athens, Greece and Italy at MACRO, Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome where the project arrived in 2019, with the exhibition The Tides / La Marea.

We reached Monica via Zoom in Washington DC, where she lives and works.

Could you tell me about your journey as an artist and how do feminism, ecological and social activism intertwine in your practice and in your life?

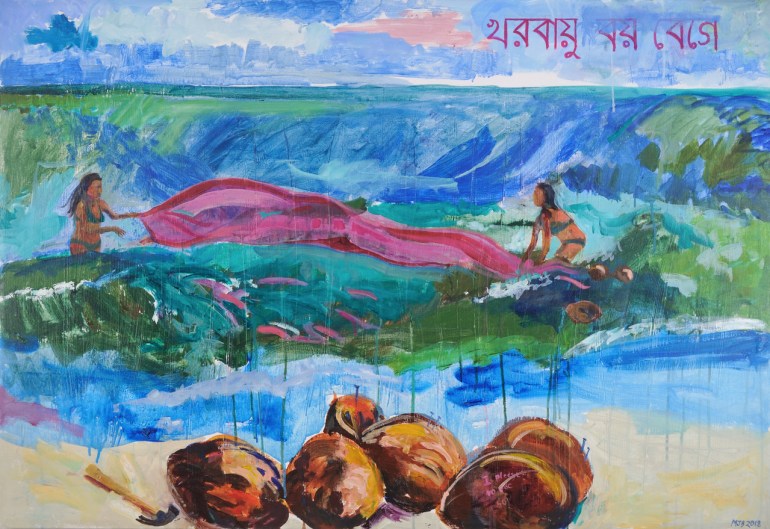

Monica Jahan Bose: Since I was very young, I was interested in landscape painting and in the natural world. My very first painting when I was nine–year old, portrayed a women’s rights march, that I attended with my mother who’s a great feminist. Both my parents were progressive leftists. Then at university I studied law and became an environmental attorney and activist. These experiences blended into my recent work, that focuses on environmental and women’s issues. My practice includes object-making, painting, printmaking and installation, but I also run a long-term collaborative eco-feminist project called Storytelling with saris.

When did this project begin and what inspired it? Your mother is an important figure in developing your Storytelling, can you tell me about it?

Monica Jahan Bose: It started eight years ago, and again, it was I partly inspired by my mother, who started an organization in Bangladesh in our ancestral village Katakhali, on Barobaishdia Island (Patuakhali District) in the Bay of Bengal.

It’s a multi-layered art, advocacy and eco-empowerment project that involves schooling for women, ecological farming, and climate adaptation skills.

Initially, I portrayed these women as the subject of my paintings, but then I thought it would be interesting to involve them directly in my practice. Originally twelve women and their families were engaged in creating collaboratively drawings, prints and writings on the saris.

These women are survivors of cyclones, storms and floods. Until relatively recently, they did not have the same access to education as men. Now they can write and read and keep climate diaries: the intent is to have a record of their daily lives through their own voices, to bring to light the struggle of a remote and otherwise unknown community.

The sari blouse and sari garment are your signature medium. When did you first think of using them as an art form? And what are the cultural values you attach to this garment in your work?

Monica Jahan Bose: I first started using the sari blouse when I was living in Paris, around 2007. My mother had sent me a blouse, and initially, I thought I’d use it as a pop art object in a new painting I had just started. The work of artist Jim Dine, whom I had met at university, and who often painted and drew bathrobes in his pop art, influenced me. But then, as I used the blouse in more paintings, it took on a symbolic meaning, standing for my identity, the ties to my culture and as a symbol for women’s bodies.

The red sari blouse, against the background of a green Sari, became a feminist flag as well. The colour red on the Bangladesh flag, which features a red disc on a green background, also stands for the bloodshed during the fight for independence of Bangladesh in 1971, when a lot of women were raped during a massive genocide.

After the war, they found places where women were held captive filled with lots of torn garments, and some of my work about gender based violence refers to that.

More recently in Storytelling I use the entire sari as a storyboard, each of my installations and performances is in continuity with previous ones.

Saris are made of unstitched six meters of fabric, possibly the most ancient precursor of many robes that came later in history, and can take many forms, representing the female body for example. Traditionally, saris are handwoven. Weaving in Greek and South Asian mythology references the continuity of life: it is a beautiful metaphor that speaks to all humanity.

Saris are never ending and renewable: Bengali women never throw it away, they recycle it. They keep saris for generations, and when they become really worn out they stack them and hand stitch them together to make Kanthas, women’s most important craft in Bengal, used as blankets, shawls or curtains.

Water has been at the center of many of your projects. In December 2019 at MACRO Museum of Contemporary Art in Rome you brought to Italian audiences a multimedia, site specific installation and a climate lab titled The Tides/La Marea, curated by Simona Amelotti. Can you tell me what was the thinking behind this exhibition and what was the Italian public’s response to your project?

Monica Jahan Bose: water has been an important element in my work as I have a lot of associations with it: my family is from an island, rivers crisscross Bangladesh. I made a series of paintings about water and climate change and also about how we are linked through water. Water is a source of life but it’s getting warmer because of climate change, it swells and evaporates and that causes devastating floods and rain.

My project last year at MACRO Museum The Tides/La Marea, reflected on rising tides, and included installation, performance, a video projection and an audio diffused throughout the museum’s atrium: a song about the tide that I sing with women of my ancestral village.

I wanted to create something that looked at the same time like rising water and a waterfall. The space of the museum is very challenging, but I was happy about the result. MACRO has a lot of public engagement, so I invited the public to join me in making the installation. I also created a floating climate lab, and I recorded testimonials about people’s experience. I collected voices from all over Italy, Europe and the world, which I may use in another work.

We were all moved by the images of Venice, about the cultural and economic loss, issues that many countries are now facing. Every island in the world has its own cultural heritage and mythologies, and if these places become inhabitable, we are looking at a massive cultural loss.

Can you describe the communities you work with and you create, both in the States and in Bangladesh, and what kind of collaborative work you have set up with these communities?

Monica Jahan Bose: I create new communities around each of my art projects. Long term, I’ve been working with the community in Katakali. We share knowledge about climate change.

They tell me about their experiences: for example, that two out of the six seasons there used to be in Bangladesh are now missing. I tell them about the causes of change, mostly about the burning of fossils fuels, as in the island they don’t really have cars or electricity.

I try to share farming skills, introducing a new type of agriculture, and planting coconut trees. The latter are dying at a faster pace because of climate change. I also teach women self-advocacy, which implies writing letters to the Government to ask for help.

In Washington DC, I’ve worked with homeless women and African- American communities. In different places, I link up with women’s organizations and environmental communities to form alliances. In my workshops, we work together on a sari and watch videos sharing information about the basic mechanics of climate change, that many people really don’t know about.

I ask people to write phrases on saris with promises about what they can do to cool the planet. In the United States, the largest ecological footprint comes from office buildings, residences and transportation, not the industrial sector.

With my practical and tactile approach, I also try to say that each of us has the power to make a difference, it is important not to feel hopeless and overwhelmed. We can make some difference in shifting quickly and dramatically how we live.

You have addressed the problem of migrants and refugees in an exhibition called Footprint-Apotýpoma in 2019, curated by Vasia Deliyianni, when the mayor’s office invited you to Athens by. The title referenced both the carbon and footprint the miles travelled by migrants and refugees. Can you briefly tell me about this project?

Monica Jahan Bose: The central idea of Footprint-Apotýpoma was the role of climate crisis in immigration. There are many reasons people migrate, but often for an economic reason intertwined with climate change: drought in many parts of the planet leads to famine, wars and displacement. In Bangladesh, we have lots of displaced farmers and fishers in coastal areas. They move to cities, and if they cannot find work, they migrate overseas. They may not identify as climate migrants or climate refugees, but climate is definitely one factor.

‘Footprint’ also referenced the idea of people’s movement across places. Apotýpoma in Greek means footprint, but also the border control finger printing; the Greek root typo, as in typography, is also associated with print-making, a reference to my printing on the saris.

It was difficult to reach the refugees community because of bureaucratic reasons, but luckily I ended up working with a refugee agency whose goal was making refugees meet with the local community and become part of it.

We created a beautiful installation of a house made of saris, and we had several workshops culminating in a performance that engaged people from Athens and refugees in writing on the theme of ‘home’ with glass markers on the windows. We had five translators, and even though there were many languages spoken, we managed to create a community.

Do you think that artists in Asia are generally closer to environmental problems than western artists?

Monica Jahan Bose: Possibly in Asia people are less separated from nature, especially in rural areas, and this may be true for artists as well. But in the general population, I think that people living in cities are the same in the East or the West.

How is it to be a feminist and environmental activist in Bangladesh?

Monica Jahan Bose: There’s a lot of women in Bangladesh involved in human rights and feminist organizations, so in this respect Bangladesh is very ‘hospitable’. But then of course there is also a very traditional and hyper-patriarchal part of the population, that finds anything that challenges these traditions is dangerous, and I guess that a much of my work could seem outrageous to some religious groups. There have been some very violent episodes in recent years, against gay activists for instance. There is tension. I want to present my work authentically, but I try to remain conscious about how my work could be understood in the West and in Bangladesh.

Many are interpreting this pandemic as a signal that the world needs a drastic reversal of the neoliberal economic system that prioritise the economic gain of the few over human survival. How do you see it? Do you think a trend reversal is really possible? Are you hopeful that the new USA administration changes this trend?

Monica Jahan Bose: the pandemic certainly has showed us that human actions do impact directly the environment. During lockdown, we have seen pollution decrease. It has also shown us we can survive with less burning of fuel, less commuting and less travel, which also means saving money. Travel is a huge part of climate crisis. I hope these realizations will lead industry and governments to different ways of using our workforce.

Office constructions especially in America have to be constantly air-conditioned because all the windows are sealed, and this is a very unsafe working environment during a pandemic. I’m hoping that this will lead to more echo-friendly architecture. We have to shift drastically in how we build and use energy in buildings.

Obviously, I’m happy about having Donald Trump and the GOP out, and that the Biden administration has said that we will stay in the Paris Agreement on climate change. But I’m hoping that there will be more. So far, the people that were announced are very competent but aren’t necessarily thinking radically differently. We have to make more dramatic shifts in how the world is working.

One reason people voted for Trump is because they wanted big change. I hope that back to business as usual is not what the new administration will do, or it may backfire again in four years. We are at a watershed moment on this planet and we need to come up quickly with new bold ideas. We need to bring in a new generation of more creative thinkers, and I hope that this will happen in time, people want proper action.

Add comment